From generous government subsidies to support for lithium batteries, here are the keys to understanding how China managed to build a world-leading industry in electric vehicles.

Tech Review Explains: Let our writers untangle the complex, messy world of technology to help you understand what''s coming next. You can read more here.

Before most people could realize the extent of what was happening, China became a world leader in making and buying EVs. And the momentum hasn''t slowed: In just the past two years, the number of EVs sold annually in the country grew from 1.3 million to a whopping 6.8 million, making 2022 the eighth consecutive year in which China was the world''s largest market for EVs. For comparison, the US only sold about 800,000 EVs in 2022.

The industry is growing at a speed that has surprised even the most experienced observers: "The forecasts are always too low," says Tu Le, managing director of Sino Auto Insights, a business consulting firm that specializes in transportation. This dominance in the EV sector has not only given China''s auto industry sustained growth during the pandemic but boosted China in its quest to become one of the world''s leaders in climate policy.

How exactly did China manage to pull this off? Several experts tell MIT Technology Review that the government has long played an important role—propping up both the supply of EVs and the demand for them. As a result of generous government subsidies, tax breaks, procurement contracts, and other policy incentives, a slew of homegrown EV brands have emerged and continued to optimize new technologies so they can meet the real-life needs of Chinese consumers. This in turn has cultivated a large group of young car buyers.

But the story of how the sector got here is about more than just Chinese state policy; it also includes Tesla, Chinese battery tech researchers, and consumers across the rest of Asia.

In the early 2000s, before it fully ventured into the field of EVs, China''s car industry was in an awkward position. It was a powerhouse in manufacturing traditional internal-combustion cars, but there were no domestic brands that could one day rival the foreign makers dominating this market.

"They realized that they would never overtake the US, German, and Japanese legacy automakers on internal-combustion engine innovation," says Tu. And research on hybrid vehicles, whose batteries in the early years served a secondary role relative to the gas engine, was already being led by countries like Japan, meaning China also couldn''t really compete there either.

The risks were extremely high; at this point, EVs were only niche experiments made by brands like General Motors or Toyota, which usually discontinued them after just a few years. But the potential reward was a big one: an edge for China in what could be a significant slice of the auto industry.

Meanwhile, countries that excelled in producing gas or hybrid cars had less incentive to pursue new types of vehicles. With hybrids, for instance, "[Japan] was already standing at the peak, so it failed to see why it needed to electrify [the auto industry]: I can already produce cars that are 40% more energy efficient than yours. It will take a long time for you to even catch up with me," says He Hui, senior policy analyst and China regional co-lead at the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), a nonprofit think tank.

Plus, for China, EVs also had the potential to solve several other major problems, like curbing its severe air pollution, reducing its reliance on imported oil, and helping to rebuild the economy after the 2008 financial crisis. It seemed like a win-win for Beijing.

China already had some structural advantages in place. While EV manufacturing involves a different technology, it still requires the cooperation of the existing auto supply chain, and China had a relatively good one. The manufacturing capabilities and cheap commodities that sustained its gas-car factories could also be shifted to support a nascent EV industry.

So the Chinese government took steps to invest in related technologies as early as 2001; that year, EV technology was introduced as a priority science research project in China''s Five-Year Plan, the country''s highest-level economic blueprint.

Then, in 2007, the industry got a significant boost when Wan Gang, an auto engineer who had worked for Audi in Germany for a decade, became China''s minister of science and technology. Wan had been a big fan of EVs and tested Tesla''s first EV model, the Roadster, in 2008, the year it was released. People now credit Wan with making the national decision to go all-in on electric vehicles. Since then, EV development has been consistently prioritized in China''s national economic planning.

It''s ingrained in the nature of the country''s economic system: the Chinese government is very good at focusing resources on the industries it wants to grow. It has been doing the same for semiconductors recently.

Starting in 2009, the country began handing out financial subsidies to EV companies for producing buses, taxis, or cars for individual consumers. That year, fewer than 500 EVs were sold in China. But more money meant companies could keep spending to improve their models. It also meant consumers could spend less to get an EV of their own.

From 2009 to 2022, the government poured over 200 billion RMB ($29 billion) into relevant subsidies and tax breaks. While the subsidy policy officially ended at the end of last year and was replaced by a more market-oriented system called "dual credits," it had already had its intended effect: the more than 6 million EVs sold in China in 2022 accounted for over half of global EV sales.

The government also helped domestic EV companies stay afloat in their early years by handing out procurement contracts. Around 2010, before the consumer market accepted EVs, the first ones in China were part of its vast public transportation system.

"China has millions of public transits, buses, taxis, etc. They provided reliable contracts for lots of vehicles, so that kind of provided a revenue stream," says Ilaria Mazzocco, a senior fellow in Chinese business and economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. "In addition to the financial element, it also provided a lot of [road test] data for these companies."

But subsidies and tax breaks are still not the whole picture; there were yet other state policies that encouraged individuals to purchase EVs. In populous cities like Beijing, car license plates have been rationed for more than a decade, and it can still take years or thousands of dollars to get one for a gas car. But the process was basically waived for people who decided to purchase an EV.

Finally, local governments have also sometimes worked closely with EV companies to customize policies that can help the latter grow. For example, BYD, the Chinese company currently challenging Tesla''s dominance in EVs, rose up by keeping a close relationship with the southern city of Shenzhen and making it the first city in the world to completely electrify its public bus fleet.

When the Chinese government handed out subsidies, it didn''t limit them to domestic companies. "In my opinion, this was very smart," says Alicia García-Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis, an investment management firm. "Rather than pissing off the foreigners by not offering the subsidies that everybody else [gets], if you want to create the ecosystem, give these subsidies to everybody, because then they are stuck. They are already part of that ecosystem, and they cannot leave it anymore."

Beyond financial incentives, local Chinese governments have been actively courting Tesla to build production facilities in the country. Its Gigafactory in Shanghai was built extremely quickly in 2019 thanks to the favorable local policies. "To go from effectively a dirt field to job one in about a year is unprecedented," says Tu. "It points to the central government, and particularly the Shanghai government, breaking down any barriers or roadblocks to get Tesla to that point."

Today, China is an indispensable part of Tesla''s supply chain. The Shanghai Gigafactory is currently Tesla''s most productive manufacturing hub and accounts for over half of Tesla cars delivered in 2022.

But the benefits have been mutual; China has gained a lot from Tesla as well. The company has been responsible for imposing the "catfish effect" on the Chinese EV industry—meaning it''s forced Chinese brands to innovate and try to catch up with Tesla in everything from technology advancement to affordability. And now, even Tesla needs to figure out how to continue being competitive in China because domestic brands are coming at it hard.

The most important part of an electric vehicle is the battery cells, which can make up about 40% of the cost of a vehicle. And the most important factor in making an EV that''s commercially viable is a battery that''s powerful and reliable, yet still affordable.

About Bangui electric vehicles evs

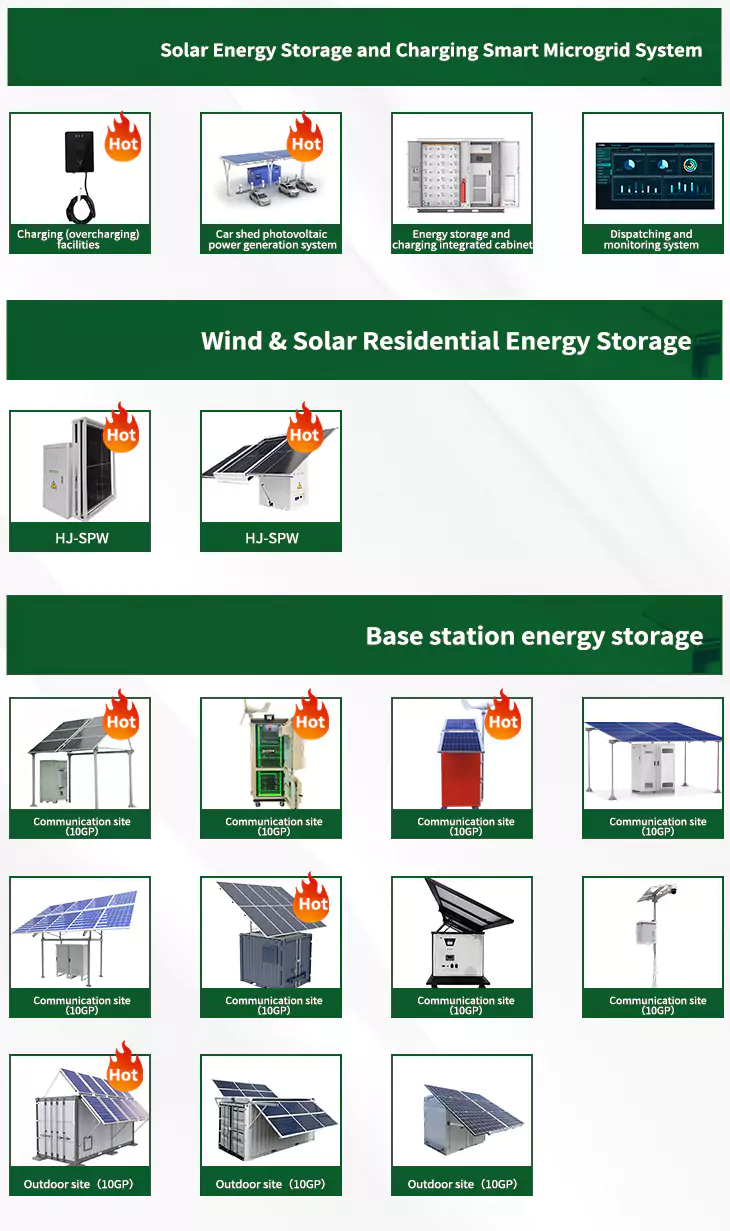

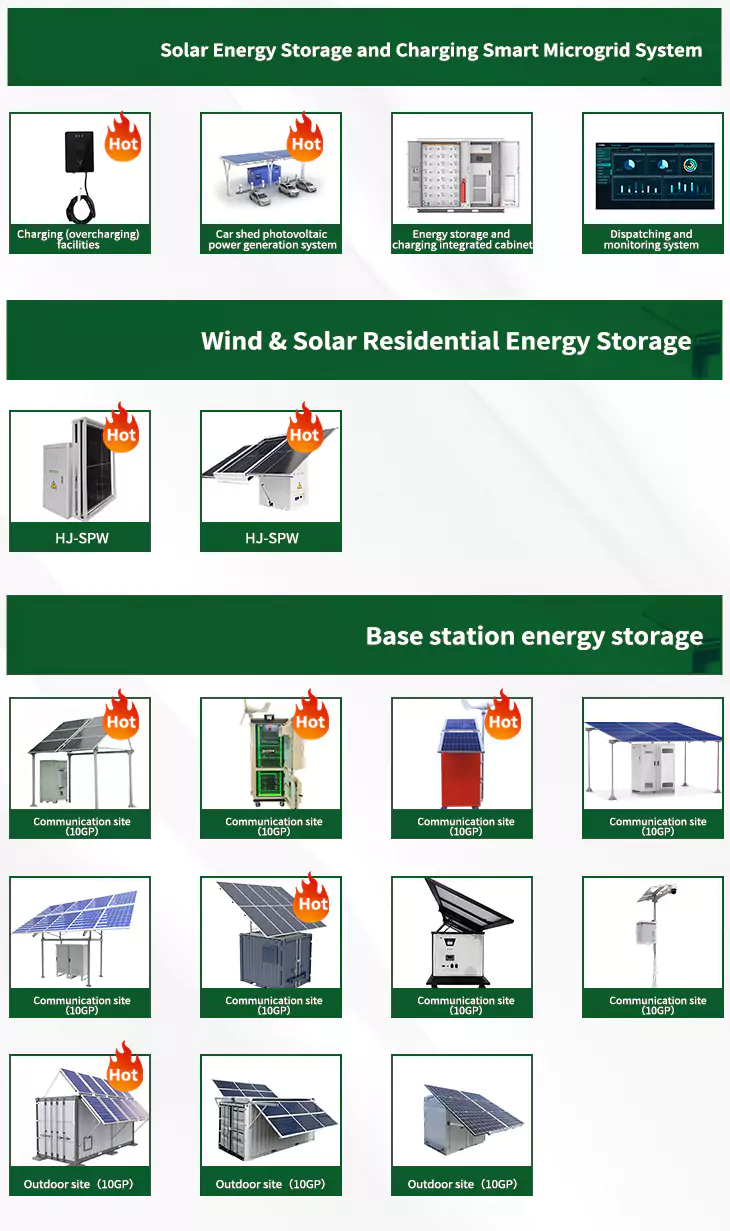

As the photovoltaic (PV) industry continues to evolve, advancements in Bangui electric vehicles evs have become critical to optimizing the utilization of renewable energy sources. From innovative battery technologies to intelligent energy management systems, these solutions are transforming the way we store and distribute solar-generated electricity.

When you're looking for the latest and most efficient Bangui electric vehicles evs for your PV project, our website offers a comprehensive selection of cutting-edge products designed to meet your specific requirements. Whether you're a renewable energy developer, utility company, or commercial enterprise looking to reduce your carbon footprint, we have the solutions to help you harness the full potential of solar energy.

By interacting with our online customer service, you'll gain a deep understanding of the various Bangui electric vehicles evs featured in our extensive catalog, such as high-efficiency storage batteries and intelligent energy management systems, and how they work together to provide a stable and reliable power supply for your PV projects.

Related Contents