In late May, Tajikistan''s government yet again announced that the country''s energy system would reconnect to the Central Asian Integrated Power System (IPS or CAPS), a network allowing states in the region to exchange electricity based on seasonal fluctuations in supply and demand. The technical process of reconnection, funded by the Asian Development Bank, was first announced back in 2018, and is already two years past the stated deadline. A response to an informal inquiry suggested that the connection, which is delayed for technical reasons, should now be completed by July 2024.

Central Asian deadlines are fluid and stretchy, like the riverbed of Amu Darya, which flows down from the Pamiris and separates the great deserts of the region. Nevertheless, Tajikistan''s intention to reconnect to the common power system, whether it takes place this summer or is postponed again, offers a strong indication of the realization by Central Asian leaders that the region''s potential can only be achieved through cooperation.

In this sense, physical geography defined the direction of the energy network based on the seasonal electricity and water needs of the industrial and agricultural areas of the region. Mountainous Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan provided hydro-generated electric power and water to downstream Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. The latter three sent coal- and gas-generated electricity to the upstream countries when water levels were not sufficient to produce electricity.

Fast-forward 15 years and the region, which sits on massive reserves of hydrocarbons and exports significant amounts abroad, is afflicted by continuous disruptions in power supply. Blackouts in major cities have become common and public discontent about energy has become a major concern. Hence, the recent efforts to reconnect Tajikistan to the IPS and thereby reinvigorate the trans-regional synergy of hydrocarbons and hydropower.

The efforts to revive energy interdependence reflect, this time around, cooperative rhetoric, which has been more apparent in recent years. Numerous diplomatic exchanges between regional leaders provided solid results in resolving sensitive territorial disputes, which for a long time bred distrust and prevented cross-border commerce and people''s exchanges. This cooperative trend is driven by economic pragmatism, but has emerged in within a more conducive regional and geopolitical climate.

First of all, Central Asia''s present leaders have increased confidence, both in their states’ sovereignties but also in their individual power. They have come to realize that the main risk to their regimes emanate from social instabilities caused by economic concerns, rather than from separatist movements allegedly supported by their neighbors. The ethnic Uzbeks in Osh, Kyrgyzstan do not want to join Uzbekistan; they want to be able to visit their relatives in Andijan by driving two hours across the border, instead of detouring for 10 hours.

The region''s present leaders seem to appreciate the importance of economic prosperity for the stabilities of their regimes, and recognize the fact that they can move toward this prosperity through increased interstate cooperation.

Thirty years of independence increased their confidence as individual leaders, in part with the passing of most of the Soviet-era cohort. No longer does personal competition for leadership, such as between Islam Karimov and Nursultan Nazarbayev, define regional dynamics. Instead, Uzbekistan''s President Shavkat Mirzoyayev, who patiently waited for the death of his isolationist predecessor before coming to power in 2016, has acted as a leading force for cooperation, opening the center of Central Asia, Uzbekistan, to the rest of the region once again.

His counterpart in Kazakhstan, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, a career diplomat who became president after Nazarbayev''s 2019 resignation, appreciates the importance of continuous communication for healthy interstate relations.

In resource-deficient Kyrgyzstan, good relations with the neighbors are essential for economic survival and for the regime stability of current President Sadyr Japarov.

The only remaining post-Soviet strongman, Emomali Rahmon of Tajikistan, also sees the benefits of cooperation, particularly as he is preoccupied with orchestrating a power transition to his, allegedly somewhat pro-Western, son. Local elites joke, "while knyaz''ya (dukes in Russian) fight, bayi (Central Asian landowners) will always find an agreement." This time around the saying might actually hold ground.

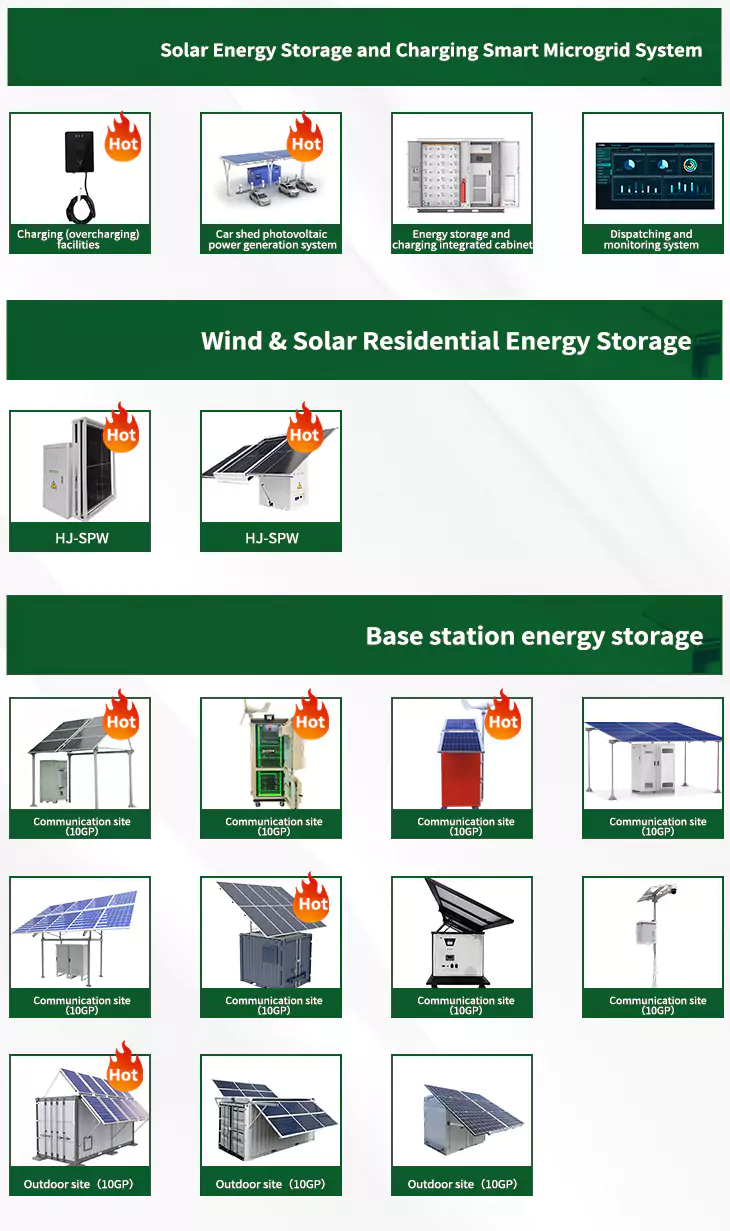

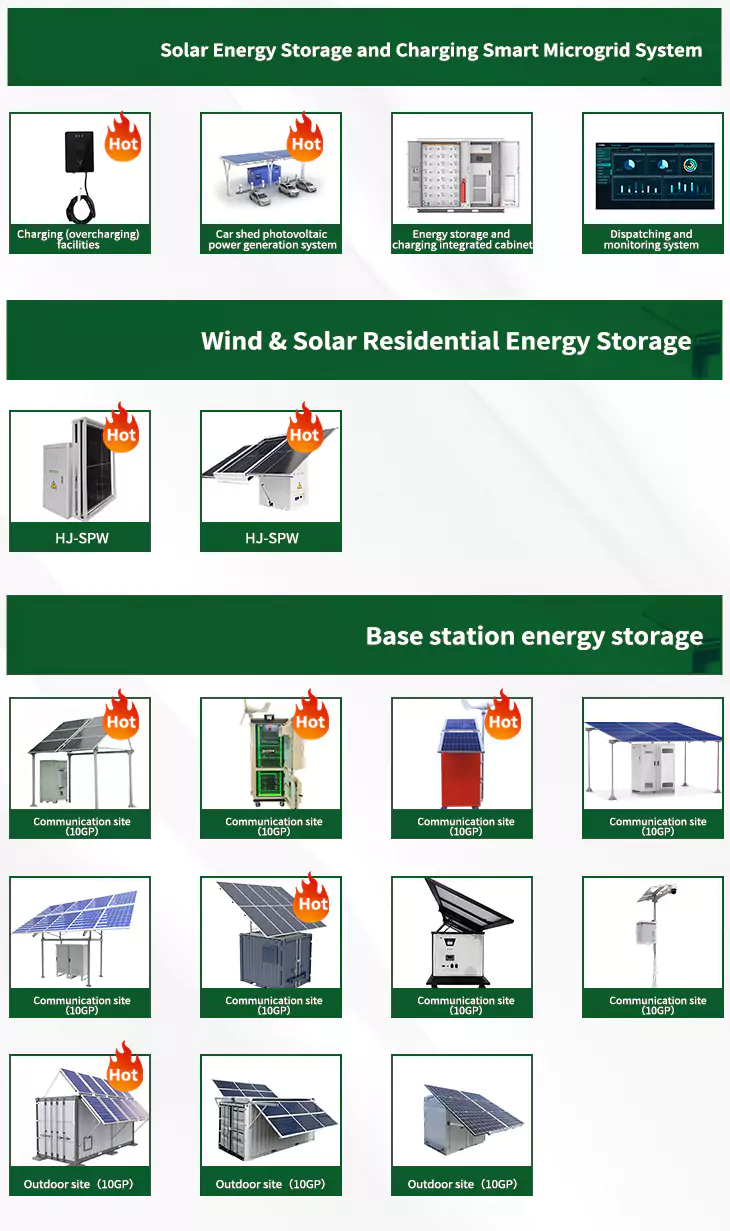

About Tajikistan energy independence

As the photovoltaic (PV) industry continues to evolve, advancements in Tajikistan energy independence have become critical to optimizing the utilization of renewable energy sources. From innovative battery technologies to intelligent energy management systems, these solutions are transforming the way we store and distribute solar-generated electricity.

When you're looking for the latest and most efficient Tajikistan energy independence for your PV project, our website offers a comprehensive selection of cutting-edge products designed to meet your specific requirements. Whether you're a renewable energy developer, utility company, or commercial enterprise looking to reduce your carbon footprint, we have the solutions to help you harness the full potential of solar energy.

By interacting with our online customer service, you'll gain a deep understanding of the various Tajikistan energy independence featured in our extensive catalog, such as high-efficiency storage batteries and intelligent energy management systems, and how they work together to provide a stable and reliable power supply for your PV projects.

Related Contents